|

Monty Roberts is een bekende naam in de paardenwereld. Ook in Nederland zweren trainers bij de Join Up of het gebruik van dually halters. Maar waarom is de "Monty Method" inmiddels achterhaald? Allereerst is het onmogelijk om het juiste te doen als we niet over de juiste/alle informatie beschikken. Door de jaren heen zijn veel principes vanuit Natural Horsemanship methoden onder de loep genomen, met schrikbarende resultaten. Dankzij research, praktische en wetenschappelijke onderzoeken van deskundigen weten we steeds beter hoe de dynamiek tussen paarden onderling en tussen mens en paard wel werkt. 'Correct Roundpenning' is een belangrijk voorbeeld; iets dat in heel veel gevallen niet correct en niet paardvriendelijk of natuurgetrouw wordt uitgevoerd. Door het paard fysiek in ruimte te beperken, een onnatuurlijke/drijvende houding aan te nemen zonder respect voor de threshold van elk individueel paard, voeren we onnodig veel druk op bij paarden die daar toch al moeilijk mee om kunnen gaan. Stress, onbegrip en angst zijn 3 dingen die mij bij ieder paard in een sessie met Monty Roberts (en Linda en Pat Parelli) zijn opgevallen en bijgebleven. Nee, het is NIET normaal dat een paard in èèn enkele sessie gerehabiliteerd is. Het is NIET normaal om een paard in stress eindeloos rondjes te laten rennen. Het is NIET normaal om zo veel onnodige druk te blijven gebruiken, laat staan continue op te voeren. Het is NIET normaal dat we onze paarden pesten om maar tot het gewenste resultaat te komen, binnen een bepaald tijdsframe en dit alles slechts "voor de show"... Om ze hun natuurlijke omgeving af te nemen en te verwachten of zelfs eisen dat zij ons leiderschap accepteren. Leiderschap = Partnerschap, plain and simple; voor een paard is er geen verschil. Bij het opvolgen van methodes als die van Monty hebben we het dus niet over deze natuurgetrouwe dynamiek. In zo'n geval hebben we het over "Bullying Into Submission". Meer lees je in het originele artikel: https://phys.org/news/2012-07-urge-rethink-monty-roberts-horse.html?fbclid=IwAR3enh-XF71O_fAvOyu38rO3lcxbRa5GOfv6mok5LTx_ADAQb8QO1u2XlqM "Volg het Paard, niet de Methode"

Love, Zoë van Mourik | Equine Trauma & Behavior Specialist www.zoevanmourik.com & www.houseofhorsemanship.nl

0 Comments

》Over waarom voerbeloningen niet altijd een goed idee is, we R+ te veel vermenselijken en daardoor alsnog te veel druk op het paard leggen & meer; "Operant conditioning, and the usual methods we employ with non-traumatised horses may not be adequate for those animals with a trauma history (Schlote,2017 aShalev et al., 1996). Generally speaking operant conditioning requires the horse to perform behaviours that can be reinforced. Traumatised horses do not offer behaviours we can easily reinforce or even would want to reinforce! Escape behaviour is often what we would see instead.These animals are often too fearful for food rewards to be effective (it also can cause approach/avoidance conflict).This means they can quickly take themselves over threshold something to be avoided. It is especially problematic if a horse has a history of food deprivation as their desire for food even a low value food/reinforcer may lead them to come outside their comfort zone or window of tolerance (Corrigan et al., 2011; Siegel, n.d.)." . Een heel duidelijk en mooi beschreven artikel dat tevens belicht waarom ik woorden als "Rehabiliteren" of "Decompressing" prefereer boven "Training". Lees het originele artikel hieronder: Trauma and Operant Conditioning : Why You Can’t Train it Away?"Operant conditioning, and the usual methods we employ with non-traumatised horses may not be adequate for those animals with a trauma history (Schlote,2017 aShalev et al., 1996). Generally speaking operant conditioning requires the horse to perform behaviours that can be reinforced. Traumatised horses do not offer behaviours we can easily reinforce or even would want to reinforce! Escape behaviour is often what we would see instead. These animals are often too fearful for food rewards to be effective (it also can cause approach/avoidance conflict).This means they can quickly take themselves over threshold something to be avoided. It is especially problematic if a horse has a history of food deprivation as their desire for food even a low value food/reinforcer may lead them to come outside their comfort zone or window of tolerance (Corrigan et al., 2011; Siegel, n.d.). It is important to recognise that the behaviours that we are seeing are attempts by the horse or dog to make themselves feel safe or it is offering them a sense of relief. Each horse or dog will have their own ways of behaving that help them to feel better this is where simply observing can be so helpful. Fear may be so all consuming it overrides everything else! Touch may be frightening and targeting may also be inappropriate. Just because the horse is on a target does not always indicate the absence of negative emotional states. Avoiding the use of a fake hand (Marder et al., 2013) is better so that they become truly used to humans using classical conditioning and later shaping once a level of physical and emotional safety has been established (Van Fleet,2010). Using non-contingent reinforcement that does not depend on the animal offering a behaviour or relaxation but instead allows them to slowly begin to form a positive association whilst remaining below or at threshold may be more helpful. This is challenging in practice though and may require some trial and error. Making use of distance with or without protected contact (Laule & Whittaker, n.d.) can also be beneficial as can awareness of the animals spatial requirements which may vary even during a session for many reasons such as changes in the environment . It is important to understand though that with traumatised horses their feelings of safety and comfort may change day to day or even hour by hour depending on other factors. Adopting a purely operant approach when working with trauma or even with other challenges for that matter fails to address the underlying emotions the horse or dog is experiencing. Emotions drive and influence behaviour , the underlying emotion and the strength of that emotion also determine how and with what intensity the behaviour is expressed. Behaviours are also communication. Simply asking a horse to stand at a stationary target or asking a dog to sit or “go to mat” does not mean that the underlying emotion has been changed or that they are now able to cope. All horses and dogs are individuals how they respond and feel will differ. This is dependent on their genetics , previous experience in particular early experiences are especially powerful and their current environment (Champagne & Curley, 2009; Raoult et al., 2017; Špinka, 2012). Understanding what they need in one moment may differ in the next . Seeking to offer support rather than immediately stepping in to modify a behaviour that is determined by ourselves to be undesirable , that is not to say that there is no role for changing behaviour particular if they are unsafe or detrimental to the horse or dog or their caregiver but any alternative should genuinely be helpful to them. Having awareness of signs of tension , stress and arousal level and tailoring the training or interaction accordingly is important in helping them feel safe enough to learn. Then positive reinforcement training in combination with meeting their physical and emotional needs with friends, forage and freedom can begin. This is an updated blog post from 2019 inspired by all of the incredible discussions looking beyond operant conditioning in particular the amazing Beyond the Operant discussions with Dr Kathy Murphy of Barking Brains, Andrew Hale of Dog Centred Care , Kim Brophy of the Dog Door and Scott Stauffer at Affective Dog Behaviour . Not to forget the always inspiring conversations I have with my colleagues at Mimer Centre on this subject. References Champagne, F. A., & Curley, J. P. (2009). Epigenetic mechanisms mediating the long-term effects of maternal care on development. In Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews (Vol. 33, Issue 4, pp. 593–600). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.10.009 Corrigan, F. M., Fisher, J. J., & Nutt, D. J. (2011). Autonomic dysregulation and the Window of Tolerance model of the effects of complex emotional trauma. In Journal of Psychopharmacology (Vol. 25, Issue 1, pp. 17–25). https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881109354930 Laule, G., & Whittaker, M. (n.d.). Protected Contact and Elephant Welfare. Marder, A. R., Shabelansky, A., Patronek, G. J., Dowling-Guyer, S., & D’Arpino, S. S. (2013). Food-related aggression in shelter dogs: A comparison of behavior identified by a behavior evaluation in the shelter and owner reports after adoption. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 148(1–2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2013.07.007 Raoult, C. M. C., Moser, J., & Gygax, L. (2017). Mood as cumulative expectation mismatch: A test of theory based on data from non-verbal cognitive bias tests. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(DEC). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02197 Shalev, A. Y., Bonne, O., & Eth, S. (1996). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A review. In Psychosomatic Medicine (Vol. 58, Issue 2). https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199603000-00012 Siegel, D. J. (n.d.). Attachment and Self-Understanding: Parenting with the Brain in Mind. Špinka, M. (2012). Social dimension of emotions and its implication for animal welfare. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 138(3–4), 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2012.02.005 Resources Affective Dog Behaviour Animal Assisted Play Therapy -Rise Van Fleet and Tracie Faa-Thompson Barking Brains Control the Meerkat Dog Centred Care Dogs Impacted by Trauma EQUUSOMA The Dog Door Mimer Centre Understand Animals https://www.facebook.com/mimercentre/ Jessie Sams (2021) Animal Behaviour and Trauma Recovery Service 𝘛𝘳𝘺𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘰 𝘥𝘦𝘴𝘤𝘳𝘪𝘣𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘦𝘦𝘭 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘐 𝘧𝘰𝘭𝘭𝘰𝘸 𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘐'𝘮 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘢 𝘩𝘰𝘳𝘴𝘦.. 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘵𝘰 𝘱𝘳𝘰𝘱𝘦𝘳𝘭𝘺 𝘥𝘦𝘴𝘤𝘳𝘪𝘣𝘦 𝘮𝘺 𝘳𝘦𝘩𝘢𝘣𝘪𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘯𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘭𝘦𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘢𝘯𝘬 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘴𝘶𝘱𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵 When I'm asked to describe my work or methods I always have to think about how to properly explain, not what I am doing, but what I am feeling. Because to me, what we feel when we're with a horse is the best guideline to follow. They will tell us exactly how they feel and what they're ready for, as long as we are open to allow ourselves to feel and think outside the box. I do like horses to have their freedom. It is etched in their eternal hoofprints, transporting soldiers, families, supplies and fighting alongside humans to protect that freedom. But who is fighting for theirs? Emotional, Mental and Physical freedom are most important to me when I start rehabilitating. I'd like a horse to feel heard, seen and understood before I even ask for anything. And as soon as we've established that baseline, I implement more freedom. Instead of trying to get closer, using more tools and putting more stuff on the horse, I like to do less. If they run away, they run away. If they aren't ready to engage in our training, we can just hang out and do whatever they feel like. It's not a bootcamp, it's a partnership How wonderful it is to honor the horse, by allowing them to make their choices in complete Freedom and let them be in charge of their own process. To offer them emotional safety and ask for nothing in return. "Follow the Horse, Not the Method"

Monty Roberts; geen onbekende naam in de paardenwereld en een waar veel van ons mee zijn opgegroeid.

Termen als een round-pen werden (in Nederland) nieuw leven in geblazen en van een Join-Up hadden we destijds nooit gehoord, behalve misschien uit de Heartland boeken van Lauren Brooks. Desondanks stonden we met verbazing te kijken hoe deze man wilde/feral paarden in 1 sessie weer gewillig en kalm leek te krijgen en ze zelfs direct kon rijden. Hoe kies ik de juiste tools?

De meeste keuzes die ik maak wat betreft (ook) de tools waarmee ik werk, maak ik grotendeels gevoelsmatig.

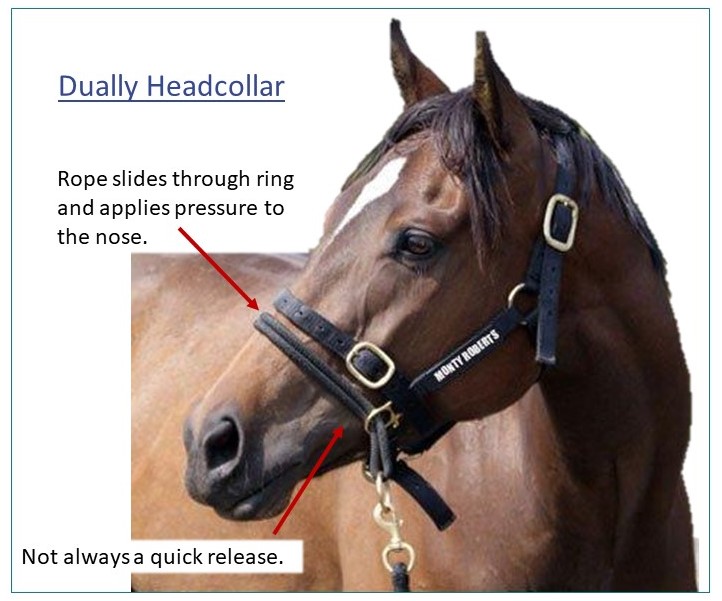

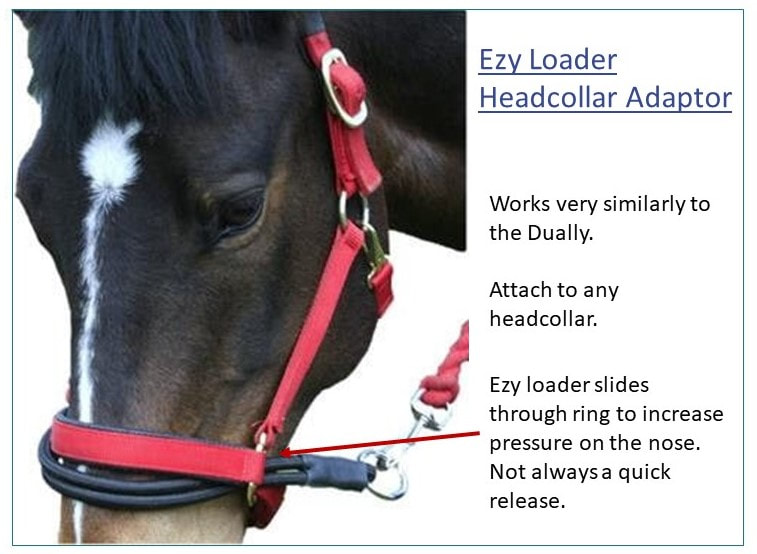

Toen ik in 2017 aan het werk ging in Amerika en te maken kreeg met echt zwaar getraumatiseerde of wilde paarden, voelde meer druk/leverage/tools juist niet logisch voor mij. Dit soort paarden (en eigenlijk alle paarden) wil ik zo veel mogelijk vrijheid geven en zo min mogelijk opties om tegen te vechten. Een optie die de Dually Halters bemoeilijkt en in sommige gevallen zelfs in zijn geheel wegneemt. Maar ondanks mijn intuïtieve (en averechtse) reacties op bepaalde onderwerpen, ben ik altijd nieuwsgierig naar de wetenschappelijke onderbouwing. Dus toen in januari 2020 een wetenschappelijk onderzoek uitkwam met resultaten die precies dat onderstreepten en bevestigen wat ik gevoelsmatig al wist, ben ik alleen maar meer gaan luisteren naar mijn eigen gevoel. Het onderzoekDoor Dr David Marlin 27 januari 2020 "TRAINING HEADCOLLARS AND THEIR EFFECT ON HORSE BEHAVIOUR - OLIVIA TURNER" *** GUEST POST *** by Olivia Turner B.Sc Hons, Animal Behaviour Consultant & Equine Bitting Specialist Handling issues are very common in the horse world and there are many gadgets and training aids available which claim to fix the problem, but what effect do these have on equine emotional state and behaviour? The gadgets utilise pressure, the more pressure you apply, the more uncomfortable it becomes for the horse. The goal being that the pressure motivates the horse to perform the right behaviour, then the handler releases that pressure. This method of pressure and release is called negative reinforcement. A stimulus is removed to increase the performance of a behaviour, e.g. applying pressure on a headcollar (HC) for a horse to stop, then releasing the pressure the second the horse stops. The horse will learn on the release of that pressure, so if your timing isn’t accurate the horse will find it harder to learn what you intend it to. Techniques (such as pressure and release) are only deemed ethical if they are proportionate to the desired response, are predictable for the horse and are released immediately upon the correct response (McLean and McGreevy, 2010). The context of the situation is very important when we’re thinking about using aversive stimuli. In a fearful situation what we really want is for the horse to relax, listen and learn something positive about what’s frightening them. Applying increasing amounts of pressure that is magnified by a training HC might get the job done, but at what cost to the emotional welfare of your horse? If you’re frightened and someone puts pressure on you, what’s your first response and how does it make you feel? There is a level where pressure becomes a punisher and it’s something I see a lot of when watching people train in training HC’s. The horse doesn’t offer the right behaviour, so they ramp up the pressure very quickly or hold it for a longer duration. What they fail to notice are the early indicators given by the horse that it wasn’t coping in that situation. Now the pressure has been escalated and they’ve made the horse feel worse about what’s going on, rather than teaching it the desired response in a more ethical way. So, the horse might perform the desired behaviour, but is experiencing emotional conflict, stress and discomfort while doing so. For example: your horse is frightened of the trailer, forcing it on by increasing aversive pressure will eventually work. However, you haven’t made the experience positive or enjoyable. Your horse is ‘behaving’ as a result of active punishment and discomfort, not because it’s truly happy at walking onto the trailer. There are a number of training HC’s on the market, perhaps the most common is the Dually Headcollar, designed by Monty Roberts. This magnifies the pressure a handler can apply in a normal headcollar and concentrates it on the nose and subsequently will create some poll pressure. Research by Iijichi et al, 2018 looked at the effects on compliance, discomfort and stress in naïve horses trained with a Dually and a normal HC in 2 novel handling tests. Their results showed that the Dually didn’t increase compliance compared to a standard HC and it caused an increase in discomfort as measured by the Horse Grimace Scale (HGS). Other similar HC’s on the market are the Ezy Loader, the Eskadron Control Headcollar and the Be Nice Halter. All give the handler a mechanical advantage and apply escalating pressure to the horse. Research has already proven that high pressures on the nose and poll caused by tight bridles and nosebands increase stress, handler avoidance, tissue damage and head shyness (Doherty et al, 2016; Fenner et al, 2016; Hockenhull and Creighton, 2013 and McGreevy et al, 2012). All things we want to avoid when teaching horses to be safe and relaxed when being handled by us on the ground. It would be interesting to see what pressures on the facial tissues are actually being exerted by these HC’s and to assess the consequences on equine emotional state and welfare. Once we understand why a horse isn’t doing a behaviour that we want, we can see things from their perspective and know which area of training needs more practice. All horses are individuals and will respond differently to various training methods, just make sure your timing is correct and you’re rewarding your horse for the behaviours you want! TAKE HOME POINTS * Increasing aversive pressure will only increase discomfort, stress, fear and pain. You might get the behaviour you want, but your horse was in a negative emotional state and therefore won’t have made a positive memory at performing that behaviour. * Identify why your horse won’t do something and focus on re-training the behaviours needed to do it. * Aim to train your horse to respond to a light aid and proof that behavioural response by practising it in a variety of situations. * Make sure your timing is accurate and reward the ‘try’ if your horse is struggling. * Be predictable for your horse and make it easy for them to get the answer right. * If your horse is struggling with something scary like trailer loading, then be realistic with what they can manage in any one session. That competition you’ve got planned might need to wait! * Don’t rush anything, be relaxed and go at the pace your horse is comfortable with. * Interested in scoring equine facial expressions for yourself? Then download the HGS app: https://awin-project-hgs.en.aptoide.com/ References: Docherty, O., Casey, V., Arkins, S., 2016. An investigation into noseband tightness levels on competition horses. Journal of Veterinary Behaviour. 15,pp.78-95. Fenner, K., Yoon, S., White, P., Starling, M., McGreevy, P., 2016. The Effect of Noseband Tightening on Horses’ Behaviour, Eye Temperature, and Cardiac Responses. PLoS ONE. 1:5,pp. 1-20. Hockenhull, J. and Creighton, E., 2013. Training horses: Positive reinforcement, positive punishment, and ridden behaviour problems. Journal of Veterinary Behaviour. 8,pp. 245-252. Iijchi, C., Tunstall, S., Putt, E., Squibb, K., 2018. Dually Noted: The effects of a pressure headcollar on compliance, discomfort and stress in horses during handling. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 205,pp.68-73. McGreevy, P., Warren-Smith, A., Gruisard, Y., 2012. The effect of double bridles and jaw-clamping crank nosebands on temperature of eyes and facial skin of horses. Journal of Veterinary Behaviour. 7, pp. 142-148. McLean, A., McGreevy, P., 2010. Ethical equitation: Capping the price horses pay for human glory. Journal of Veterinary Behaviour. 5,pp. 203-209. Paarden zelf geven dus ook de voorkeur aan een trainingshalster zonder hefboomwerking/leverage: "Their results showed that the Dually didn’t increase compliance compared to a standard HC and it caused an increase in discomfort as measured by the Horse Grimace Scale (HGS)." Touwhalsters, kaptomen en/of nylon/biothane halsters zijn fijnere en veilige tools om mee te werken en communiceren, doordat er geen hefboomwerking aanwezig is wanneer we de fysieke druk opvoeren. De zogenoemde 'consequentie' als het paard tegen de druk in beweegt, blijft dus uit. Zoals met meer tools het geval is zal de Dually in de juiste handen geen schade aanrichten; zolang deze niet ingezet wordt bij zwaar getraumatiseerde of wilde paarden want hun 3 Second Window is ontzettend klein! Dit betekent dat de quick release van -in dit geval- een Dually meer schade dan goeds aan kan richten, waardoor het fijner kan zijn jezelf bekend te maken met tools die te allen tijden toepasbaar zijn en op ieder individueel paard. Naast het feit dat ik het persoonlijk niet fijn/eerlijk vind om met extra/veel druk te werken, heeft werken op gevoel echt mijn voorkeur; en 'Feel can be taught, but not always learned'. Wat het dus moeilijker maakt om 'het juiste te doen' of om te bepalen wanneer een tool zich 'in de juiste handen begeeft'. Want wie beoordeeld en beantwoord deze vragen en situaties? En is dat wel objectief? Als je moeite hebt met het kiezen van de juiste/meest vriendelijke/eerlijke tools om mee te communiceren en werken, helpt het wellicht om aan te denken aan deze quote, die mij helpt om dingen in het juiste perspectief te (blijven) zien: "You will never have to force anything that is truly meant to be" "Increasing aversive pressure will only increase discomfort, stress, fear and pain. You might get the behaviour you want, but your horse was in a negative emotional state and therefore won’t have made a positive memory at performing that behaviour." Nog zo'n waardevolle zin uit bovenstaand onderzoek, die belicht waarom ik niet achter principes sta die gedrag 'shapen' of 'redirecten'; zo ontstaat inderdaad het gewenste gedrag, maar vanuit welke emotie stamt dit? Acceptatie, omdat het paard het samenwerken leuk vindt? Of irritatie en tolerantie, omdat het paard onder jouw druk uit probeert te komen en zich vanuit stress/angst/kwaadheid overgeeft? 'Volg het paard en niet de methode' is dus ook toepasbaar op de tools waarmee we werken en als we eerlijker en met een open mind durven kijken naar onze paarden, laten zij hun gevoel vaak al tijdig aan ons merken. De massa

Iets waar we bij het uitkiezen van tools misschien niet zo snel/lang bij stilstaan, maar zo belangrijk is; de massa van het object!

Persoonlijk geef ik bijvoorbeeld de voorkeur aan een lichtgewicht halster, zonder hardware, zonder leverage en van niet te zacht of hard materiaal. De Dually checkt dus alle punten aan die ik persoonlijk probeer te vermijden; een handige test om even te checken of de tools waar je voor gekozen hebt ook daadwerkelijk passen bij jou/jouw training. Een voorbeeld uit de praktijk, via een collega (vertaald); 'Ik heb mijn paard nu twee jaar, ze is bijna drie. Ik heb Monty's boek gekocht om haar te kunnen trainen en ik begon met een geknoopt touwhalster in plaats van de Dually. Inmiddels heb ik er 1 aangeschaft maar alleen het geluid van het hardware maakt haar zo nerveus, het duurt weer erg lang voor ik haar kan overtuigen dat het veilig is. Ze is nog jong en heel intelligent, ze volgt me overal en als ik haar touwhalster om wil doen komt ze naar me toe en stopt ze zelf haar neus door het halster!

Een voorbeeld van hoe een paard zelf dus aan kan geven zich wantrouwend te voelen tegenover een nieuwe situatie; in dit geval het introduceren van een nieuw trainingshalster. In de video hieronder zie je hoe Walter op een soortgelijke manier reageert op zijn kennismaking met een kaptoom. Let op hoe ik te werk ga wanneer Walter (vanuit wantrouwen) weg stapt.

|

Details

AuthorZoë van Mourik: Equine Trauma Specialist, Behaviorist Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

|

KvK

81860277 BTW NL003612667B82 IBAN NL75KNAB0416741983 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed